By James Rodgers

For those of us of an age to have known only peace in Western Europe,

the centenary of the end of World War I is a an opportunity to learn something of the extreme consequences of the failure to solve political differences peacefully. And when the world marked the 100th anniversary of the Armistice, millions fell silent to remember the pain and sacrifice of that conflict.

But another anniversary that fell this year – that of the end of the British Mandate for Palestine in 1948, a seminal moment in a conflict that continues to this day – has been largely ignored. It should not be. Britain’s role was pivotal – and, if it is forgotten in the UK, it is remembered in Middle East.

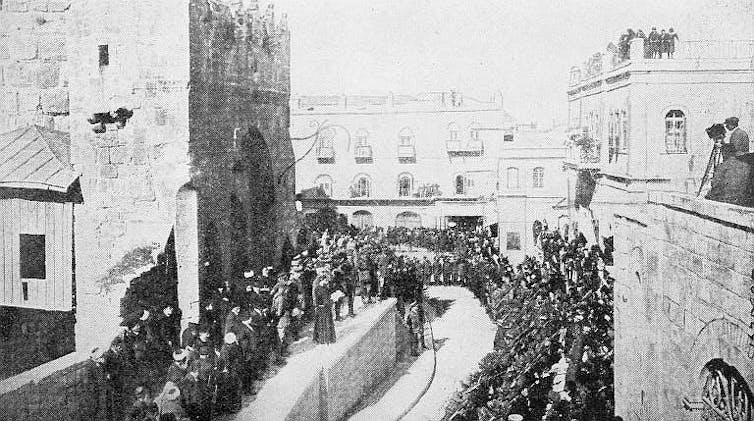

For one of the consequences of the end of World War I was the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The December before the Armistice in November 1918, troops under the command of General Sir Edmund Allenby (nicknamed “The Bull”) captured Jerusalem. After the end of the war, The League of Nations “mandated” (handed over) what was then Palestine to British rule. That rule lasted until 1948. Then the British withdrew. The region’s Jewish and Arab populations were left to to fight it out. The Jewish forces prevailed and, in May 1948, the State of Israel was declared.

The conflict is remembered by Israelis as the War of Independence; by the Palestinians as “al-nakba” (the catastrophe). In Britain – whose retreat after a period during which “the purpose of the mandate was never entirely clear to most of those serving in Palestine”, as Naomi Shepherd put it in her 1999 book Ploughing Sand: British Rule in Palestine – it is barely remembered at all.

Read more:

Nakba day in Palestine – past catastrophe, future conflict?

In a sense, this is all the more surprising because of the scale of British involvement. The numbers are staggering today. The National Army museum website gives a figure of 100,000 British troops in Palestine in 1947 – compared to a total of 78,000 fully trained troops in the entire British Army in 2017.

In another sense, it is not. The task faced by the mandate authorities was not easy. They left the region riven by conflict which continues to this day. Seeking international Jewish support during World War I, Britain had – in the words of the late historian Eric Hobsbawm – “incautiously and ambiguously promised to establish a ‘national home for the Jews’ in Palestine”.

The Balfour Declaration – as that pledge was known – was made in 1917. Its centenary in 2017 was barely noticeable compared to the attention the Armistice has generated. Like the end of the mandate, the Balfour Declaration is an anniversary Britain has mostly preferred to forget. The same cannot be said in the land that was Mandate Palestine.

Read more:

A century on, the Balfour Declaration still shapes Palestinians’ everyday lives

No brass bands

As a correspondent newly arrived in Gaza to take up a posting during the second Palestinian intifada, or the uprising against Israel, I was soon welcomed by an elderly resident of a refugee camp – and then chastised by the same gentleman for the Balfour Declaration. The year was 2002, but he traced his wretched fate – his breeze-block house had just been demolished by the Israeli Army – to that document from 1917.

In his memoir, Ever the Diplomat, the former British ambassador to Israel, Sherard Cowper-Coles, recalled an encounter he witnessed between the then Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon and the British Middle East envoy, Lord Levy. An increasingly undiplomatic exchange ended when Sharon’s “massive fist came thumping down on the desk”, as he shouted: “The British Mandate is over.”

תא, CC BY-ND

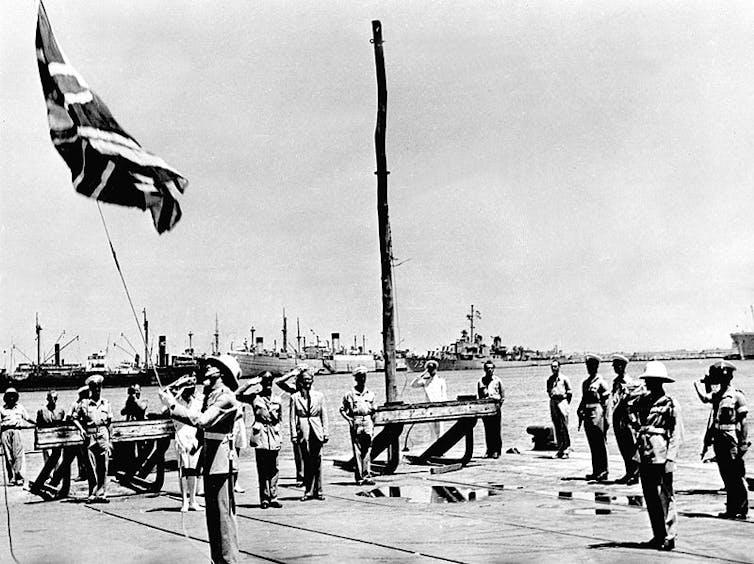

It is hard to imagine now, but when the mandate did end in 1948, it was a huge story in the British press. Research for my book, Headlines from the Holy Land: Reporting the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, led me to archived newspaper articles where the first draft of the history of that era was written. The morning that British rule ended, May 14 1948, the Daily Mirror did its best to rouse patriotic pride:

When British rule began, says the Colonial Office, Palestine was primitive and underdeveloped. The population of 750,000 were disease-ridden and poor. But new methods of farming were introduced, medical services provided, roads and railways built, water supplies improved, malaria wiped out.

The next day’s Daily Mail painted the stirring picture of the “weather-beaten, sun-dried Union Jack” which had flown over British Headquarters in Jerusalem being brought back to “the airways terminal building at Victoria” in central London.

Where the story has found its way into contemporary newspapers it has had a fraction of the attention granted to the end of World War I in Europe – a lack of public commemoration which suggests a combination of ignorance and shame.

“There were no brass bands playing when they came back. They were treated as if they’d been involved in something dirty”, the organiser of the Palestine Veterans Association told the Sunday Times recently.

Ignoring anniversaries such as these – especially at a time when the poppy appeal is given ever greater public prominence – amounts to selective commemoration, which acts against learning from military and diplomatic mistakes.![]()

James Rodgers, Senior Lecturer in Journalism, City, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.